We’ve seen the images and heard the stories: turtles caught and choked in the plastic rings from six packs; sixty pounds of plastic and other debris discovered in a deceased whale; massive islands of garbage floating in the ocean, such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, estimated to be twice the size of Texas.

Plastic waste invades our planet, and the problem goes way beyond what meets the eye.

Our rivers and seas are teeming with microplastics — tiny plastic particles less than 5 mm in length. They come from cosmetics, synthetic clothes, degraded plastics, and have been found in virtually every part of our planet, from tropical sand and coastal waters, to Alpine soil and arctic ice.

Microplastics’ diminutive size makes them less noticeable than larger plastic debris, but potentially more deadly. Once ingested or inhaled, the plastic particles — and the chemicals they may carry — can accumulate up the for chain, causing adverse health problems and impacting entire ecosystems.

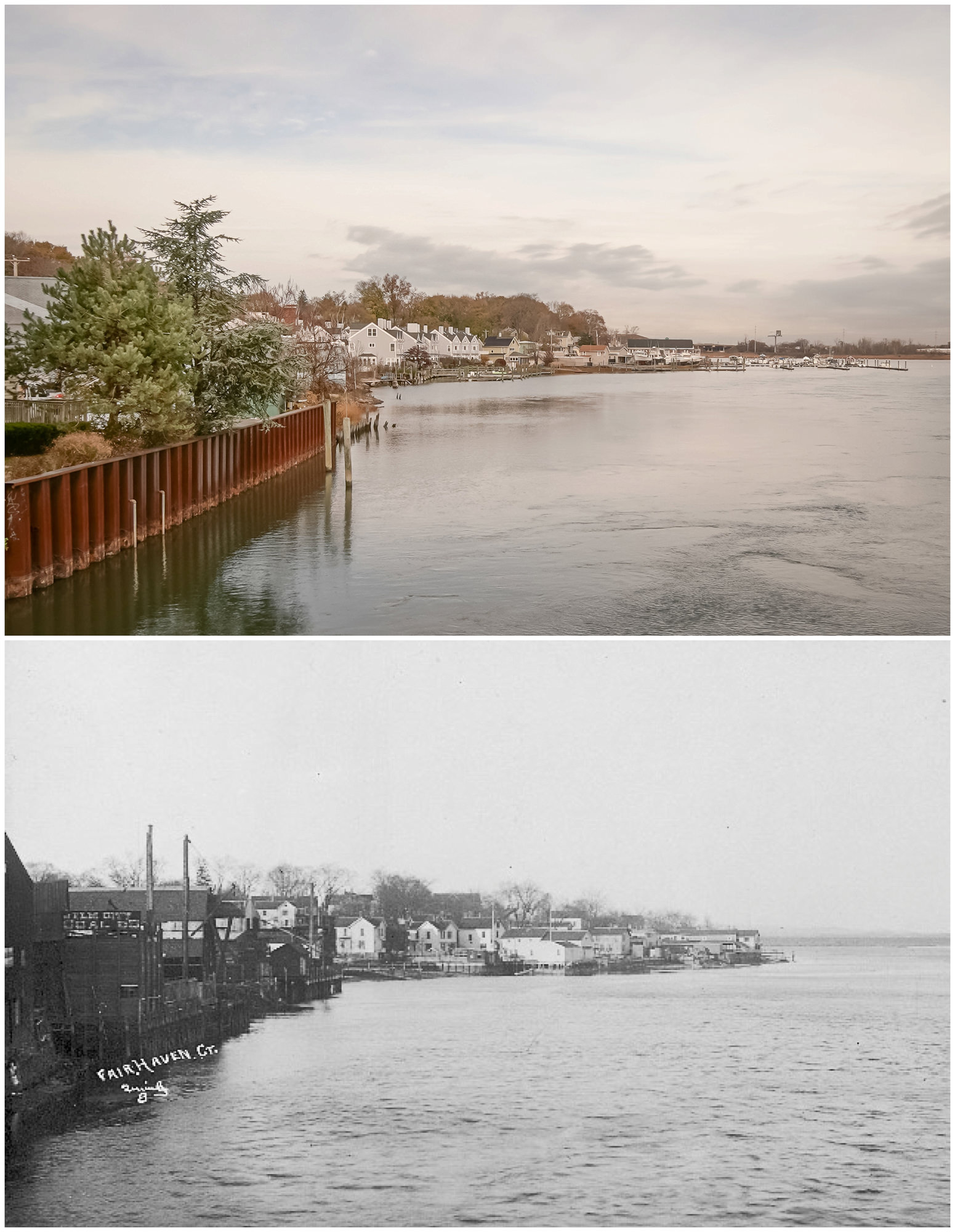

Quinnipiac River Fund supports numerous projects focused on understanding microplastics in the Quinnipiac watershed, including a Southern Connecticut State University study of the seasonal variation of these microplastics at waste water treatment facilities in North Haven and Meriden, conducted by Anthony Vignola and Vincent Breslin of the Werth Center for Coastal and Marine Studies.

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have been identified as one of the primary sources of microplastic contamination. Vignola’s study notes that though many WWTPs, including North Haven and Meriden, may have high efficiency rates for removing contamination, these systems are not specifically designed to remove microplastics. Plastic particles, and the problems they create, are quite literally falling, or rather flowing, through the cracks. Furthermore, because of the tremendous volume of micro plastics introduced into these WWTP systems, even small percentages of unfiltered plastics can still have significant environmental consequences.

Within the 11.6 million gallons of wastewater treated each day in Meriden, 746,000 microplastics are discharged, leading to an annual impact of more than 272 million microplastics. In North Haven, only 3.1 million gallons are treated daily, and with it a release of 200,000 microplastics, and an annual total of 72 million.

That’s nearly 350 million microplastics deposited into the Quinnipiac River each year from these two facilities alone. There are three additional WWTP’s discharging into the Quinnipiac, which means many hundreds of millions of microplastics polluting her water.

Unfiltered microplastics are only part of the problem, Vignola explains. Even the filtered microplastics can become problematic. These particles get trapped and accumulate in biosolid sludge that is regularly removed from the facilities and often used as fertilizer for farms or forests. If this waste is spread in a watershed, the accumulated plastics have the potential to directly reenter the waterways.

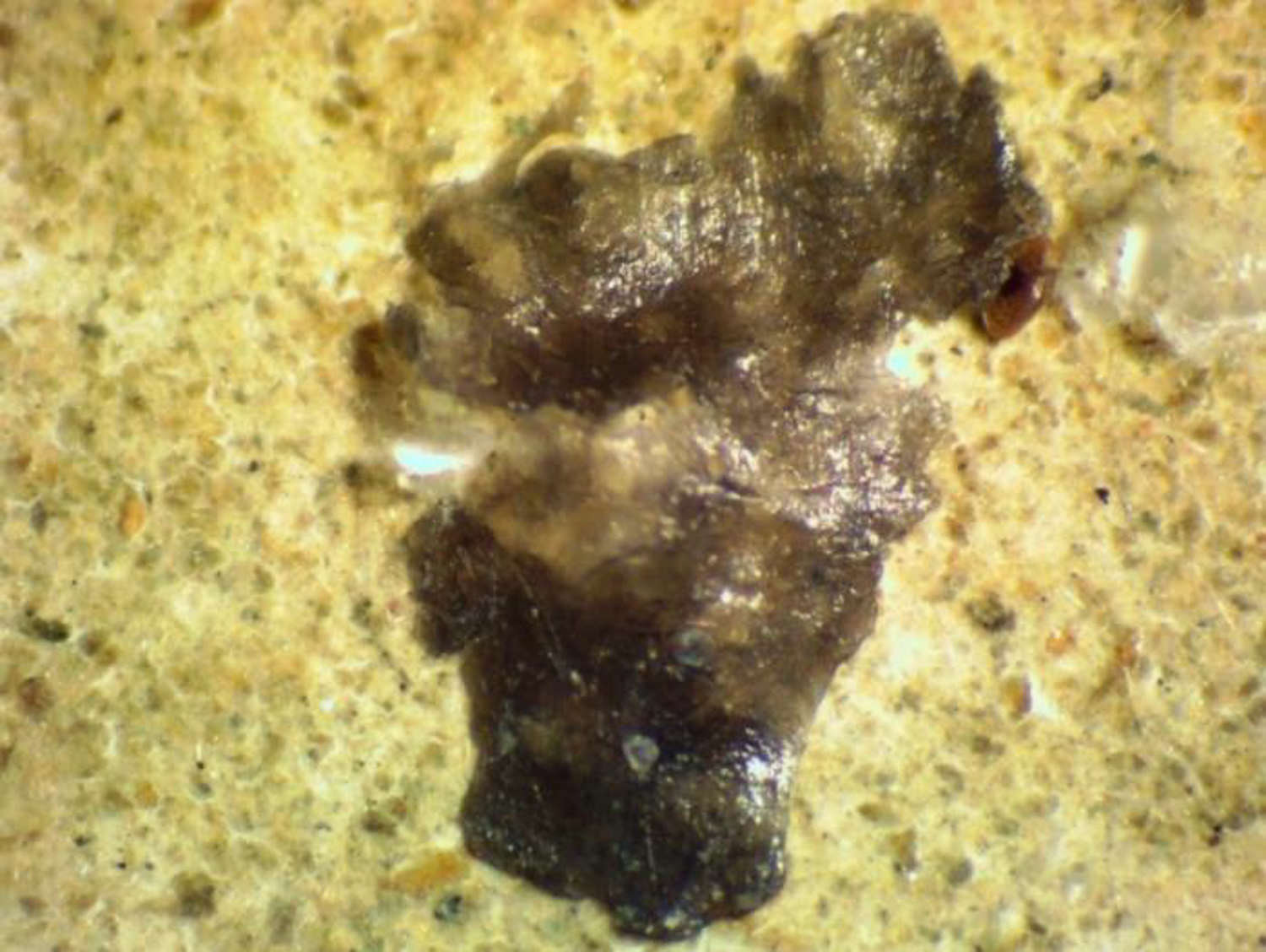

Microplastics come in four main forms: films, fibers, fragments or beads. However, Vignola reports that 74% of all plastics found during his study were microfibers, which “supports the growing body of evidence that mechanical laundering of synthetic clothing is releasing many contaminant fibers.”

“Estimates have shown that a single article of synthetic clothing has the potential to release more than 1,900 fibers per wash (Browne et al., 2011) and a 5 kg load of household laundry may release more than 6,000,000 fibers in one wash cycle (De Falco et al., 2018).”

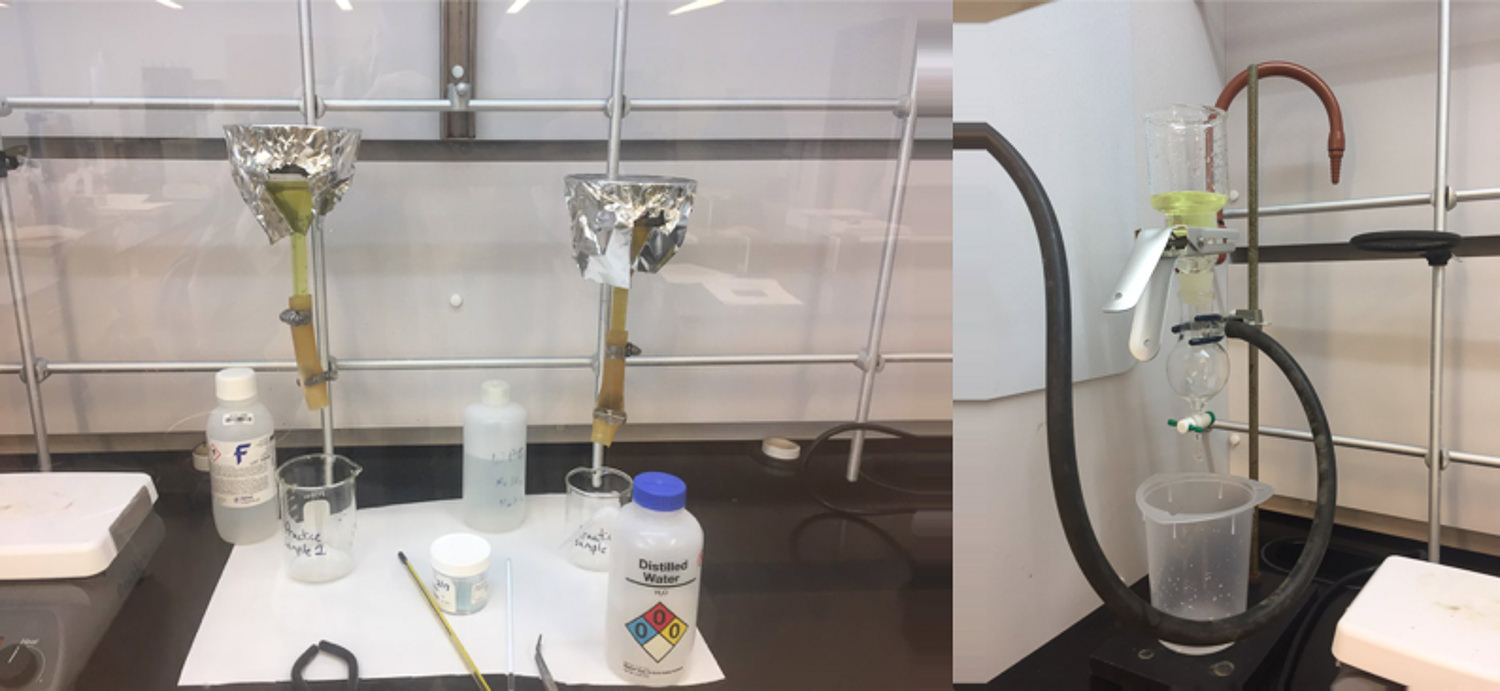

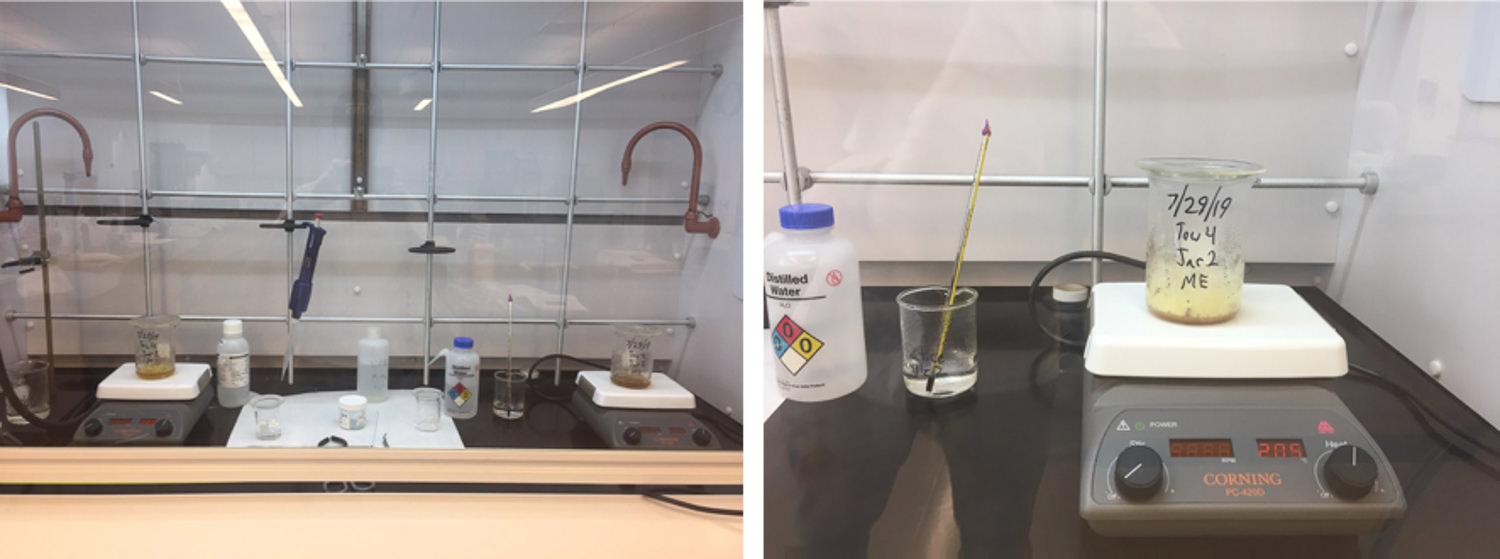

Vignola and Breslin conducted four seasonal samplings (May, July, November, February) of the wastewater discharge at each site during the course of 2019 – 2020. Microplastics were then extracted, identified, categorized and calculated using a variety of factors, including wastewater flow rate, seasonal temperature, as well as particle type, size and color.

The results at both sites revealed a trend between microplastic concentration and seasonal temperature. Though the trend was statistically significant in Meriden and slighter in North Haven, both showed increased concentrations during the winter and spring season — when fleece and other cozy synthetic favorites abound — supporting the hypothesis that the variation could be related to outerwear choices and laundering. However, Vignola noted, other international studies have produced contradictory results, with concentrations higher during warmer months, prompting consideration of the impact of other geographical factors — such as precipitation, evaporation, and flow rates.

Regardless of the extent of seasonal variations, microplastics, specifically fibers, are a growing problem. The annual production of synthetic fibers grew from 1.9 million tonnes in 1950 to 45.3 million tonnes in 2010 and the industry is still expanding. This study affirms the need for “increased accountability placed on apparel manufacturers who are responsible for using synthetic materials during production.”

As with other areas of plastic consumption, consumer knowledge and choices are also paramount to reducing microplastic contamination. Small changes, implemented by many, can add up to make a big difference. The SCSU study provides some guidance, including:

Using cold water and fast wash cycles to reduce water volume

Washing synthetic clothes less often

Using products designed to capture microfibers while laundering, such as Cora Ball or Lint Luv-R, which were 26% and 87% effective respectively and removing microfibers

Purchasing products made from non-synthetic materials

“Results of this study confirm that treated municipal wastewater is a significant source of microplastics to the Quinnipiac River, and ultimately, Long Island Sound. Financial support provided by the Quinnipiac River Fund was critical for the conduct of this research and will lead to management actions to improve the water quality and reduce microplastic impacts to regional waterways.” – Vincent Breslin, co-coordinator of the Werth Center for Coastal and Marine Studies