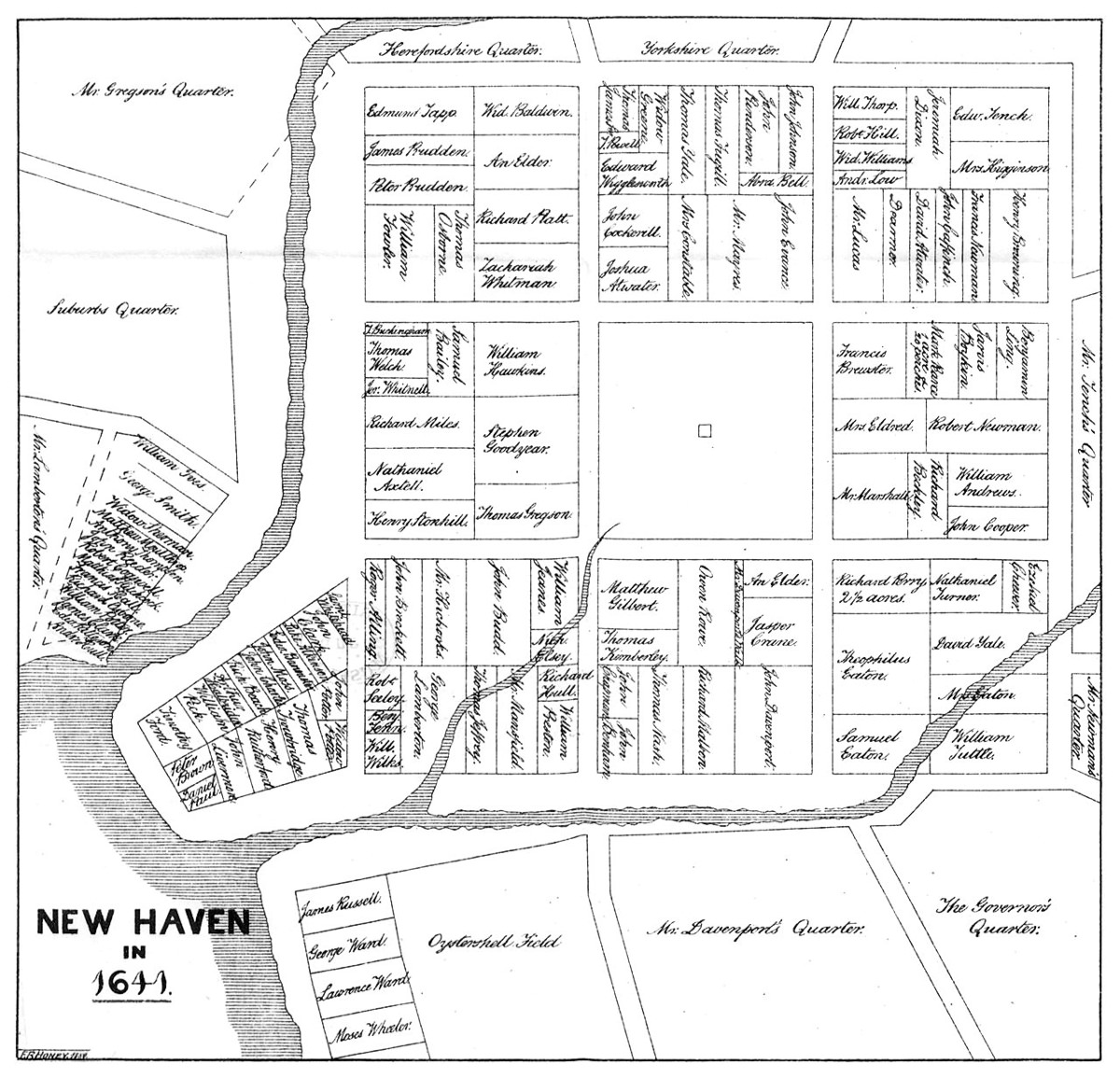

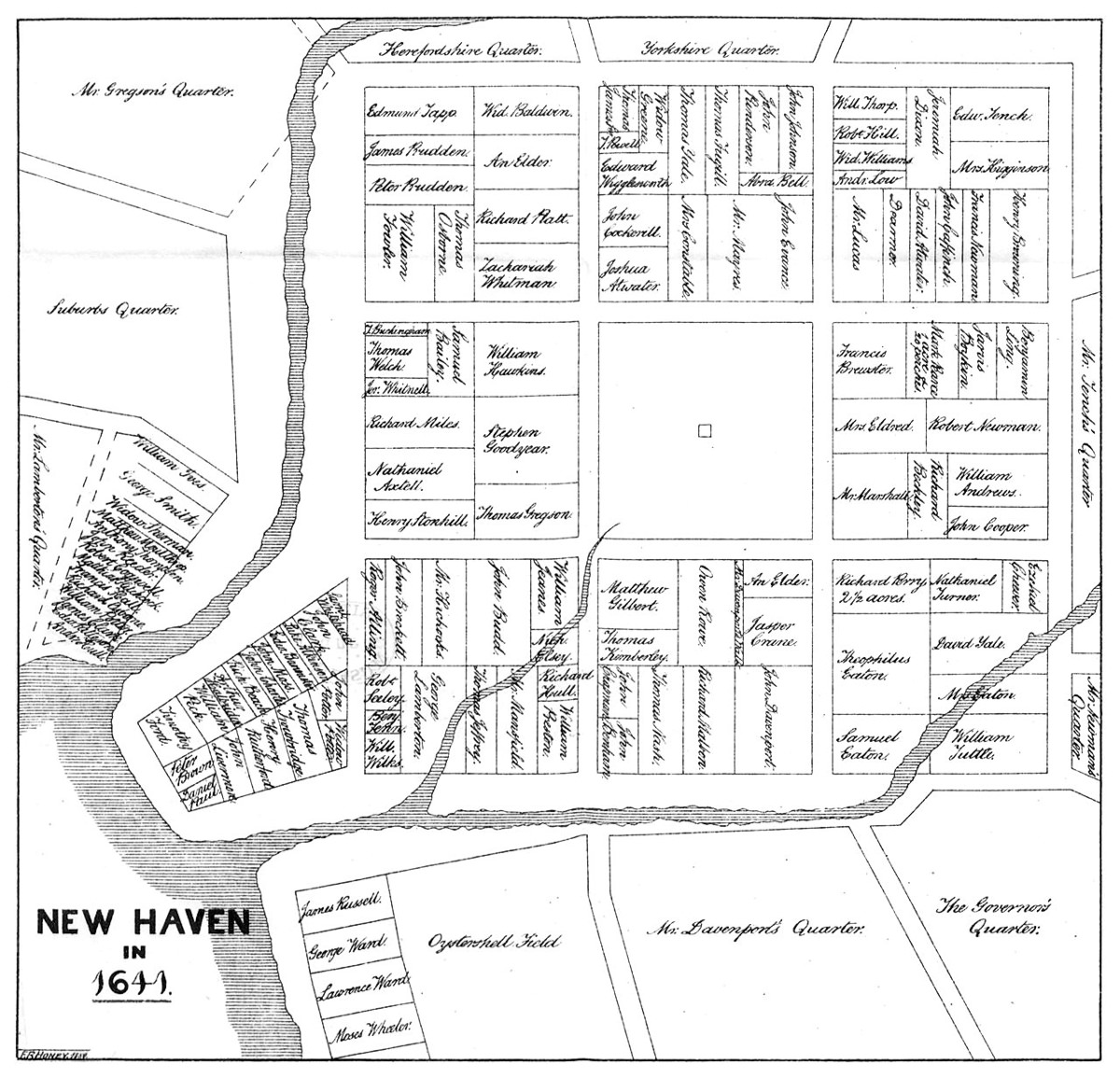

Once upon a time there was a city that loved the water. And the water made her great.New Haven’s waters (a protected harbor with three tributary rivers) drew settlers to her side. A village formed. In 1638, early colonists established a nine-square central block by the ocean’s edge. The town “stood by the harbor [and was] placed as close to the water as ground would allow and wedged into angles of the two creeks, thus maximizing water frontage.”(Elizabeth Mills Brown, New Haven: A Guide to Architecture and Urban Design)

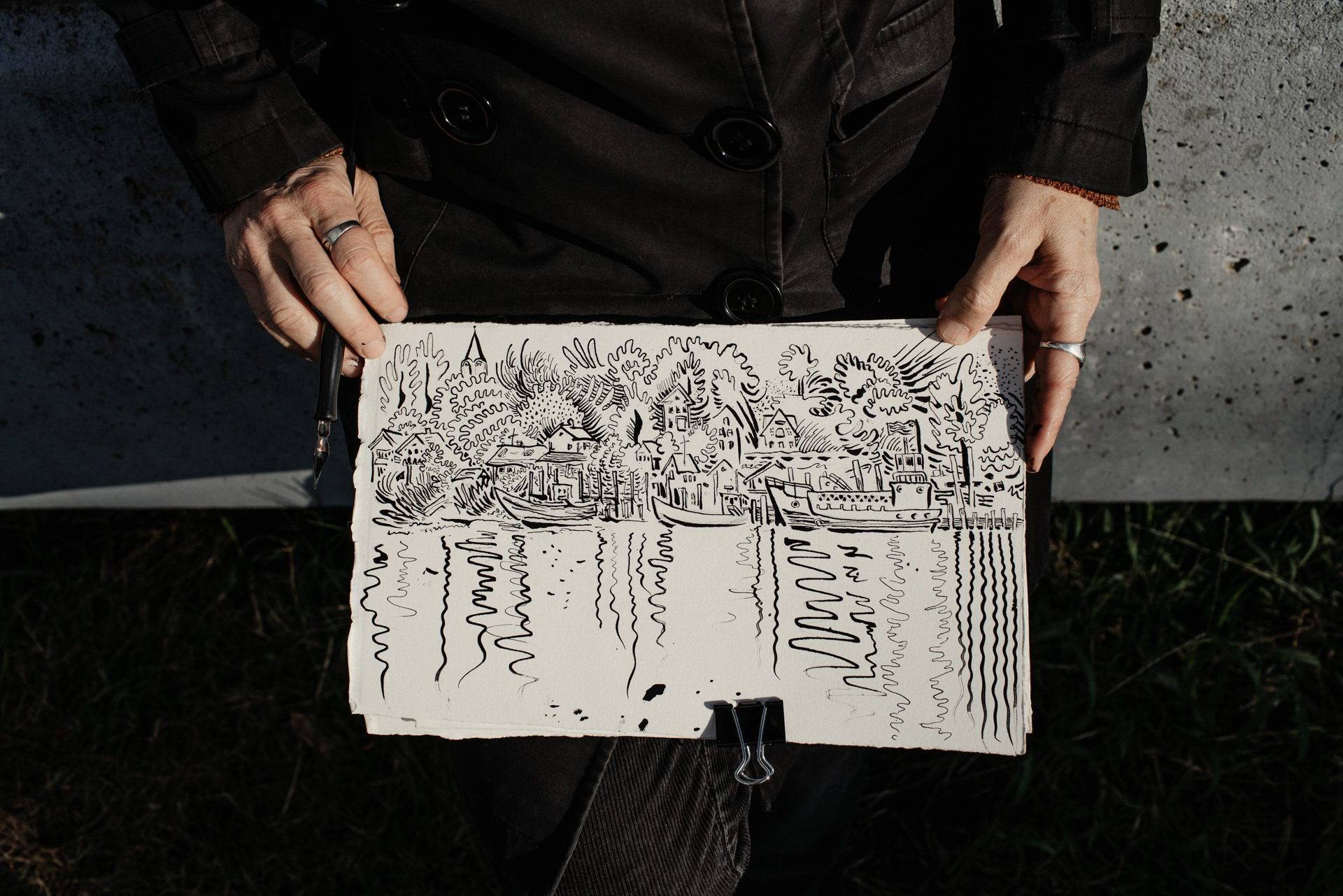

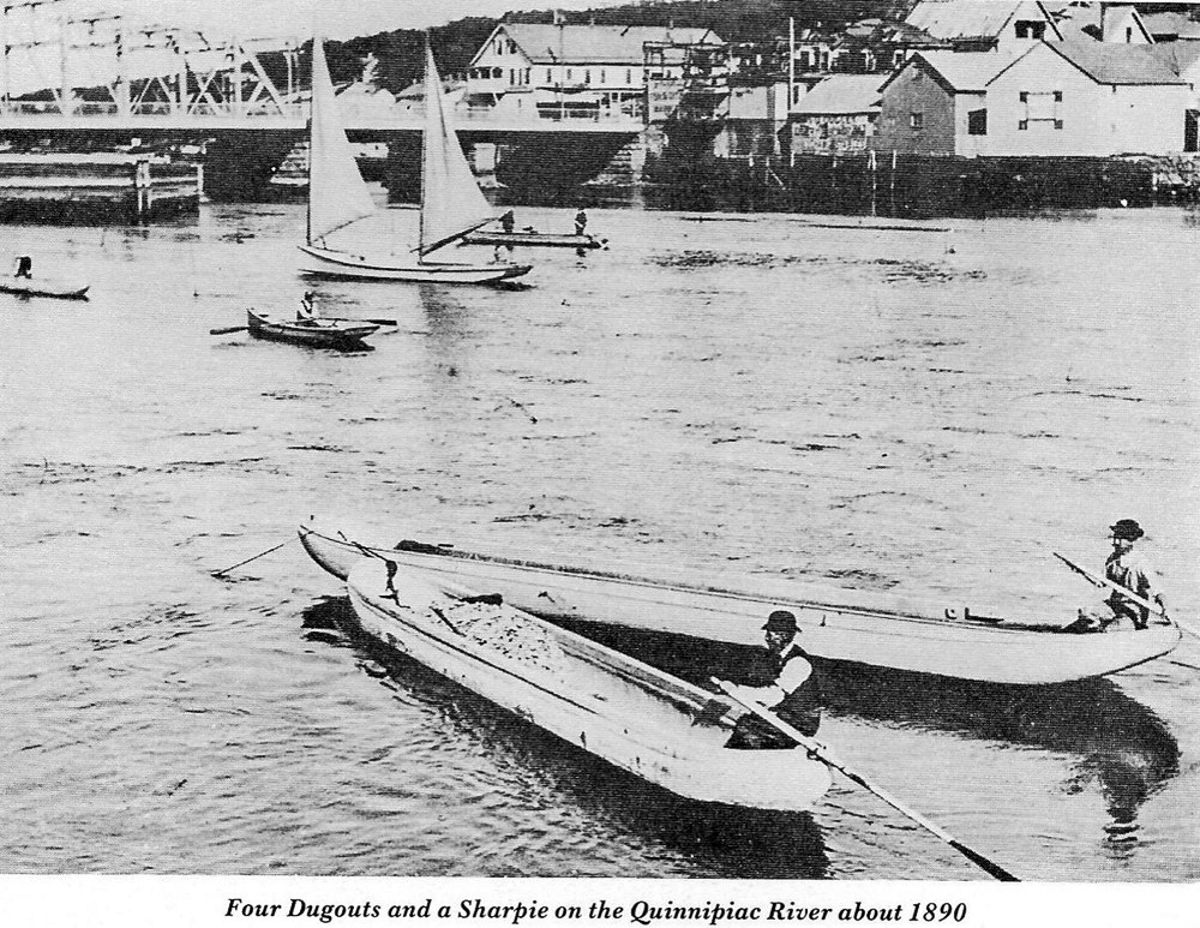

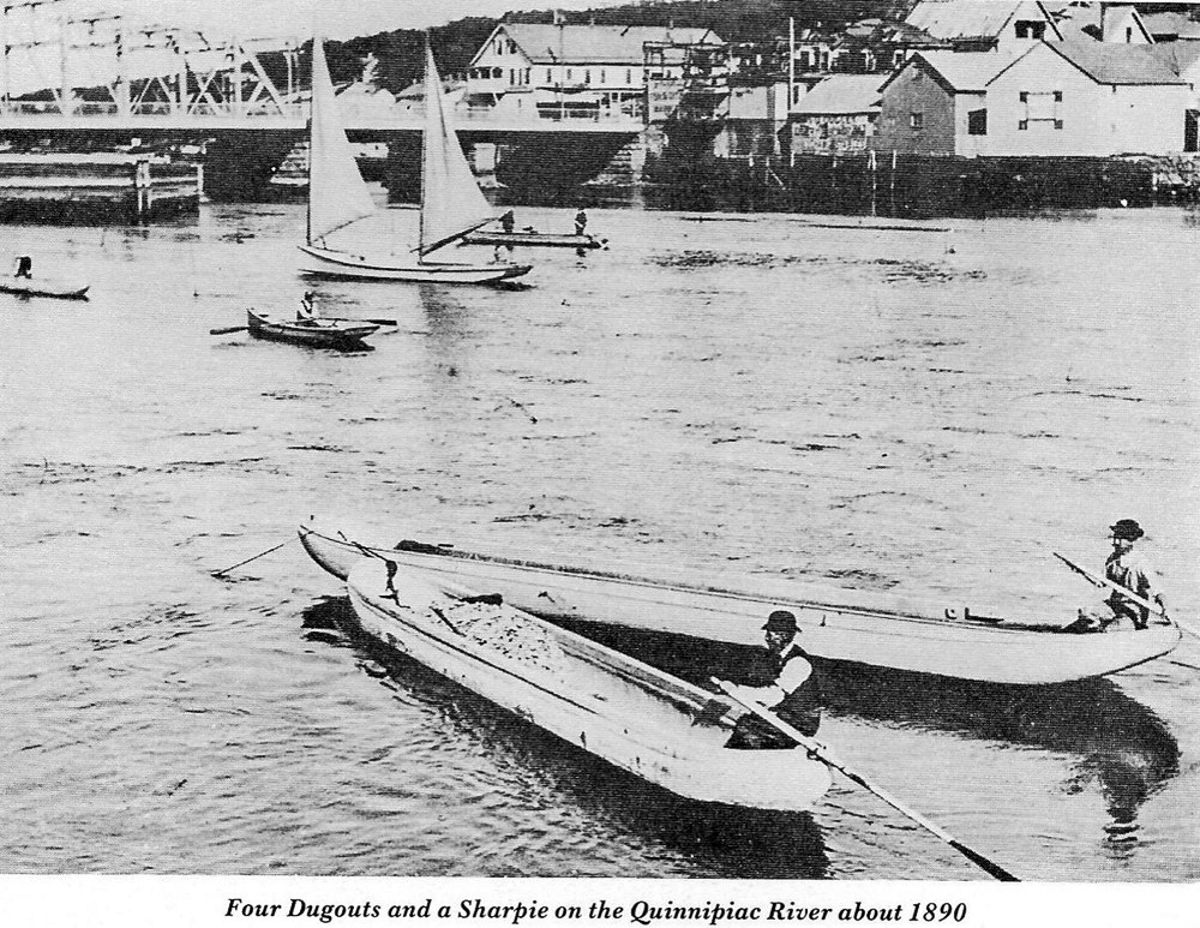

As the years progressed, New Haven’s sea-side identity developed: ocean-borne trade boomed, a world-class oyster industry developed, ship-building and watch houses dotted the banks, the harbor bustled with sloops, schooners, steamboats and sharpies: a long narrow flat-bottomed fishing boat claimed to have been built in Fair Haven in the mid 1800s.

Though maritime industries flourished, the shallowness of the bay frustrated sea commerce. In response, creeks and tidal flats were filled-in, and wharves lined with warehouses, taverns and shops extended into deeper waters. The longest — aptly named Long Wharf — stretched from the junction of Union and Water Streets into the harbor. In the 1820’s it reached a final length of ¾ mile, making it the largest in the country at the time.

New Haven’s love affair with its water did not depend on industry alone. Throughout the late 1800s water-based recreation became increasingly popular in New Haven, and, by 1900, recreation was considered one of the most important uses of the harbor. Steamboat excursions to New York became common, waterside hotels were constructed, and New Haven’s coastline boasted acres of parks and beaches for bathing and picnicking, including: City Point’s Bay View Park, a shady marine park of more than 23 acres; 30 acres on the eastern shore of the harbor encompassing historic Fort Nathan Hale and the Palisades, known for having some of the “best sandy bathing beaches;“ and, Waterside Park, which provided the city’s easiest access to the coastline recreation, offering 17.5 acres of parkland created after the harbor’s mudflats were filled-in.

Rowing became a popular pastime after a Yale junior brought a second-hand, four-oared Whitehall boat named Pioneer to New Haven in 1843. Within weeks, other students purchased similar craft and by the year’s end, the first American college rowing clubs had formed at Yale — their main function to facilitate informal skill races and pleasure cruises to coastal spots. A decade later, the hobby had grown to a serious collegiate pastime. In 1853, Yale officially organized its “Navy” for racing and began hosting the “Annual Yale Commencement Regatta” in the harbor. Soon after, Yale constructed its first boathouse — a rough structure on the Mill River above the Grand Street Bridge. However, given its location above the high tide mark, the boats had to be hand carried down the banks, which, at low tide, became a notoriously messy and muddy affair. In 1862, Yale secured the funds to construct a much-needed new facility, one that they heralded as the best boathouse in the country. Yet this structure soon revealed its own deficiencies. Built directly over the water, the house required that crew lower the boats through trap doors, climb down ladders, walk the keelson to their seats and then push clear of the piles before inserting oars into the oarlocks — an inconvenient system that brought its share of misadventures.

In 1875, Yale built its final, and best, Mill River boathouse, located at the east end of the bridge crossing Chapel Street. With ample space, storage for 100 boats, and broad floats allowing for easy launching, the wooden building served the college successfully for decades, until saltwater and weather took their toll. “In February 1909, The New York Times reported that Yale’s first practice had been canceled when many floor beams in the existing boathouse were found broken.” (New York Times, Christopher Gray, Boathouse Built for the Bulldogs Is Soon to Bow Out, February 19, 2006)

Fortunately, fundraising had already begun for a new boathouse at the mouth of the Quinnipiac — an elaborate masonry building designed by the firm of Peabody & Stearns, costing $100,000 in total, and named after George Augustus Adee, a devoted oarsman from Yale’s class of 1867. The college began using the new facility in 1911, but Adee’s boathouse days were short lived. After only five years, the growing busy-ness of the harbor prompted Yale to move its varsity teams to the Housatonic River. The rest of Yale’s rowing teams soon followed.

Yale sold the building in the 1950s and it was used mainly as office space until its demise in 2007 as part of the Pearl Harbor Memorial Bridge project. Demolition of the Adee boathouse was an architectural loss for the City, but when it comes to New Haven’s water-based identity, a much greater loss occurred decades earlier, with the construction of the original Q Bridge and Connecticut Turnpike. To accommodate the highway, hundreds of acres of the harbor were filled, distancing downtown from the water. And the interstate’s location itself — running alongside the newly created shore — further severed the City’s connection to its coastline.

While it’s not possible to turn back time and remove these physical barriers, today, a new project in the Long Wharf area hopes to turn the tide on this separation and rekindle the bygone romance of city and sea.

Currently under construction, the Canal Dock Boathouse will open “New Haven’s waterfront for adventure, discovery and growth” by creating a community-based boathouse with access, activities and programs around the water.

Owned by the City, the boathouse will be operated by Canal Dock Boathouse, Inc, (CDBi) a nonprofit established in 2013 by several members of the New Haven community recruited by the City Plan Department with a mission to increase education and awareness of Long Island Sound and improve public access to water.

The new boathouse will provide ample space and amenities to make this mission a reality. The 30,000 square foot facility sits atop a 1.12-acre platform and features a waterfront promenade, boat storage bays, handicap accessible ramps for canoe and kayak launching. Activities hoped for include: kayak and paddle board rentals and lessons, a dragon boat club, rowing and sailing, an indoor rowing studio, free programs for public school students, event spaces, and interpretive displays about New Haven’s harbor history and environment.

The boathouse’s name honors its historical location: the former Canal Dock where the Farmington Canal (and later the rail line that replaced it) met the harbor. The building itself also pays homage to a New Haven harbor legacy, that of Yale’s boathouses of old — specifically the Adee — from which architectural elements, including terra cotta finials, bulldog gargoyles and large frame from its entry portal, were salvaged are incorporated by architect Rick Wies into the building’s prominently modern design.

The $41 million project included federal funding to mitigate the impact of the Interstate 95 expansion project, which razed the Adee Boathouse. To weather the inevitable super storm, the boathouse required special architectural and engineering considerations including steel pilings driven 100-plus feet into the ground and, in the case of a hurricane, breakaway walls on the first floor.

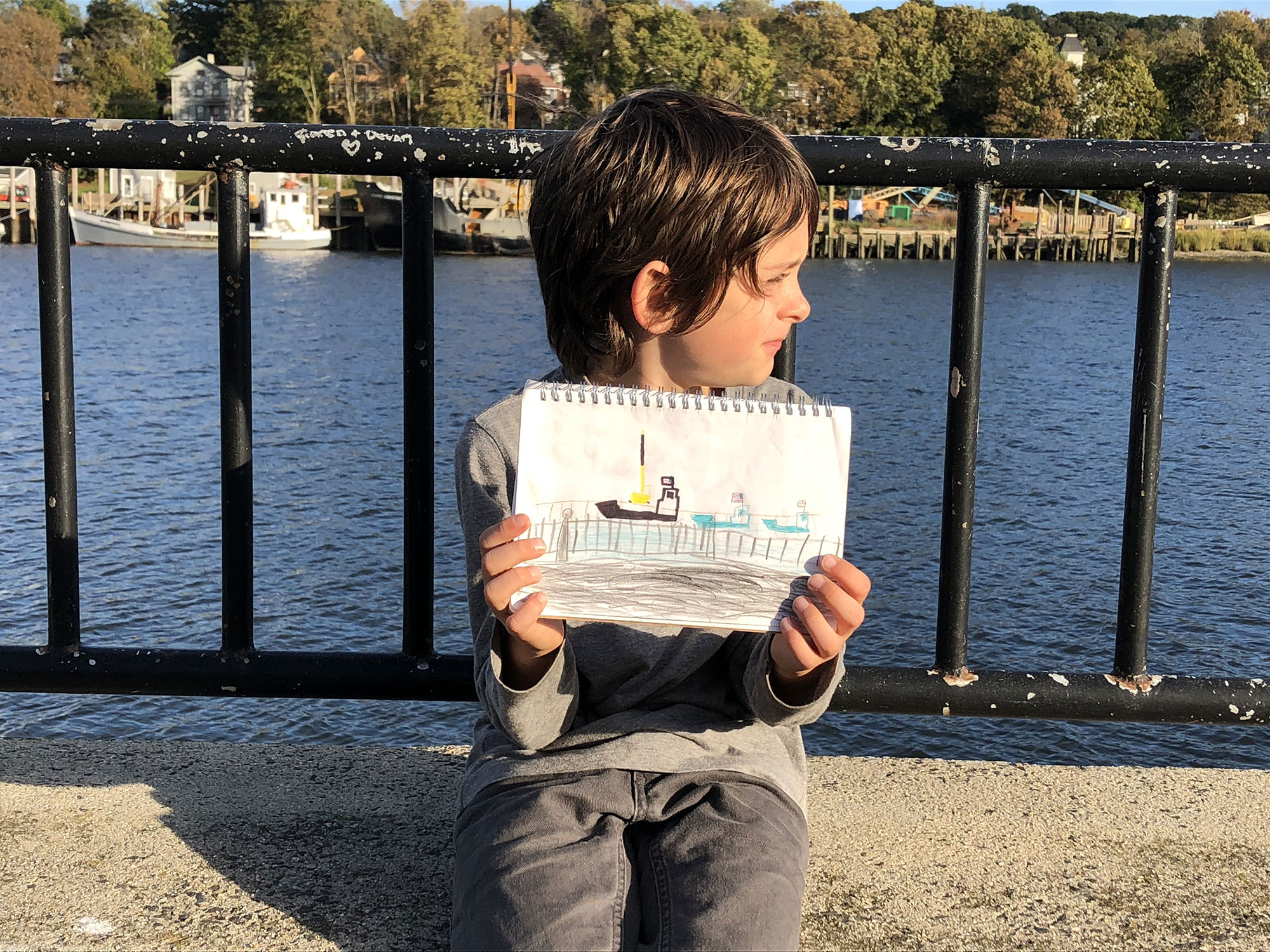

The project broke ground in September 2013 and is expected to be complete late in 2017, with on-water programs beginning in 2018. In the interim, CDBi — ready to get its oars wet — launched indoor rowing programs at the Metropolitan Business Academy and James Hillhouse High School and outdoor rowing programs at the Quinnipiac River Marina, including an immersive “Intro to Rowing” summer camp for youth in 7th – 11th grade.

“Having Canal Dock here for the last two years has been a real pleasure since it brings more people down to the water,” said Marina owner Lisa Fitch. “The affect is contagious! When you see rowers out there on the river it is just beautiful! The Q-River can accommodate a lot of different things…the river and the rowers are a nice match.”

While rowing has lead the way, kayaking, sailing and other water-related experiences are on the horizon; new access and new opportunities that give the Elm City a chance to begin a new chapter in its salty story…

Once upon a time there was a city that loved the sea…

Canal Dock Boathouse Inc received a Quinnipiac River Fund grant in 2017 to support start up staff to expand public access to rowing and other non-motorized watercraft, to grow participation in the annual dragon boat regatta, and to maintain a partnership with the University of New Haven, which will offer programs in environmental education to the general public.