On Duty with New Haven’s Bridge Tenders

“Everybody wonders who lives in the house,” said Mike Dorsey, one of New Haven’s ten bridge tenders who keep New Haven’s moveable bridges moving. While not a residence per say, the curious orange building perched in the through-truss of the Grand Avenue Bridge serves as a home away from home for the bridge tenders on duty. Similar control houses are located on the Chapel Street and Ferry Street bridges.

But what’s life like for the ones who keep watch above the rivers?

“It never closes,” Mike explains. 7 days a week. 24 hours a day. 365 days a year a bridge tender is available to ensure that boats can pass to and from the harbor and the Quinnipiac and Mill Rivers. A division of New Haven’s public works, bridge tenders operate the city’s three movable bridges: the Chapel Street and Grand Avenue swing bridges which pivot at the center to open and the Ferry Street double-leaf bascule bridge which uses a counterweight for its upward swing. The Tomlinson Bridge on Route 1 represents another type of movable bridge, a vertical lift bridge, but being state-operated, it does not fall under city jurisdiction.

New Haven’s bridge tenders work all three city bridges in three shifts. Each bridge is staffed for the first two shifts: 5 am – 1 pm and 1 pm – 9 pm, with only the Chapel Street Bridge manned during the third shift, 9pm – 5 am. As such, third shift duties include leaving the Chapel Street post as needed to open the other two bridges for any late night boat traffic.

Moveable bridges play a critical role in preserving the character of the Fair Haven and Fair Haven heights community. Whether its tugboats, barges, oyster boats or personal fishing craft, to maintain a vibrant water-based community, the boats must get by. And when they do, the bridge tenders know them by name – both the boats and their operators. “We know everybody that comes through here,” said Mike. “We have a good relationship with all the boats”

While the vessels appreciate the bridge tenders, vehicles and pedestrians don’t always share the sentiment, especially when the bridge opens during peak traffic. But despite the inconvenience, the bridges form and function still inspire much public appreciation. The Ferry Street and Grand Avenue bridges in particular, both built as replicas of the original bridges 1920 and 1900 bridges respectively, add scenic beauty and are key features in the Quinnipiac River Historic district.

Anthony Lesko, one of the city’s newest bridge tenders, has a long family history in the Quinnipiac community. “I grew up in the neighborhood,” he said, explaining that his family has lived in the same house on Hemmingway for generations. “My grandfather told me stories that they used to ride the bridge…and now I get to open them.” Of course, Anthony’s job includes preventing others from following in his grandfather’s bridge-riding footsteps.

Still new to his role, Anthony receives lots of questions when people learn of his occupation, some of the most common being, “How do you know when to open the bridge?” and, “Is it difficult?”

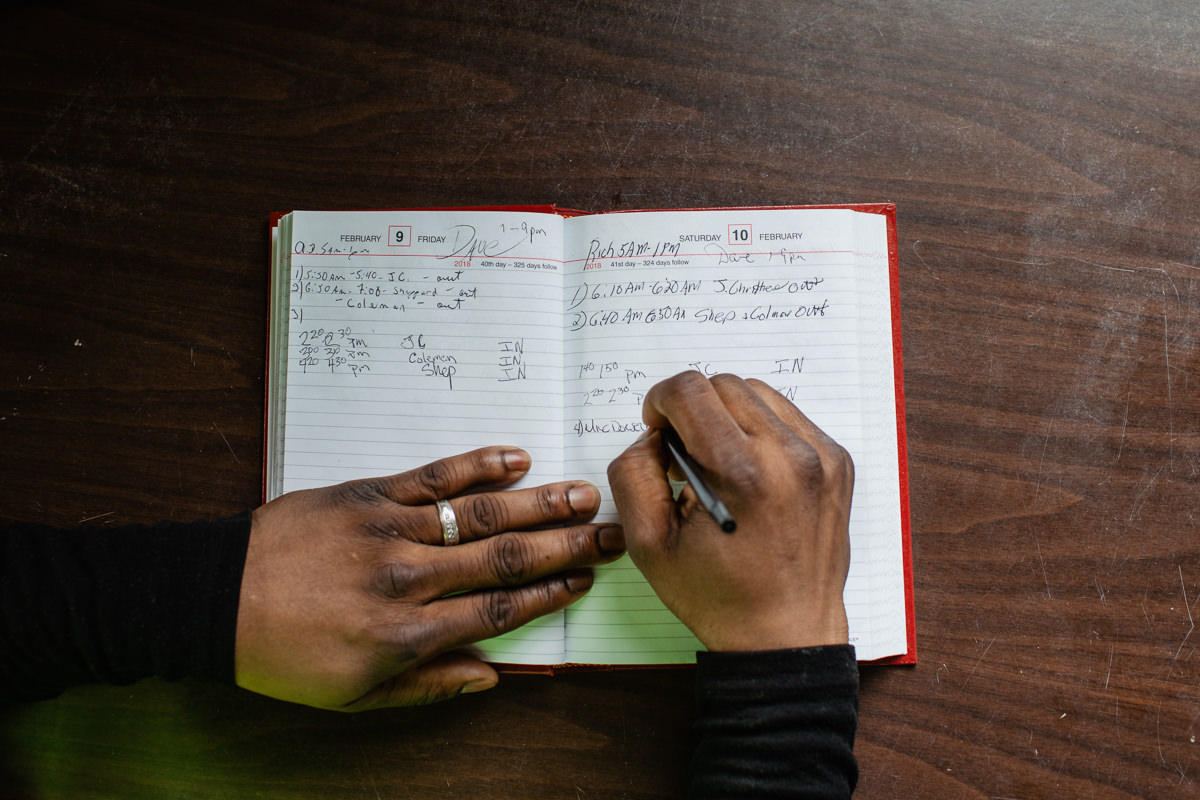

Requests to open the bridge come by phone call (with the phone number posted on signs located on the pier of each bridge) or, more commonly, by radio. When a request comes in, the bridge tender first calls fire communications to inform them of the opening so that emergency response can be diverted to a different route. The tender then enacts a visual check to make sure the bridge is clear. Depending on the bridge, the opening itself requires a series of 9 – 12 buttons or levers. Once the boat passes through and confirms it’s cleared the bridge, the bridge tenders close the bridge and lift the gates. A final call to fire communications announcing traffic completes the process.

In addition to ensuring that the bridges open and close properly, designated bridge tenders provide routine maintenance, which includes cleaning and lubricating the wedges and the fittings (or the expansion-bearing assemblies) and cleaning debris from the bridge drainage system. Sometimes the bridge tenders encounter some unexpected “duties,” such as calling animal control for a stray dog in danger of slipping through the bridge fence or chasing away the intrepid raccoons that climb the trusses, explains Bob Bombace, who may be more keen to notice the four-legged intruders considering his previous position as an animal control officer.

Some seasons also bring unexpected sights — such as a sweltering summer day when the fire department had to hose down the overheating metal trusses of the Grand Avenue Bridge or Christmas of 2017 when Santa Clause traded sleigh for boat and sailed into the Marina — but overall most days are rather routine. Daily bridge openings range from four on a slow day on the Grand Avenue Bridge to upward of ten on a busy day for the Chapel Street Bridge. Since each opening takes approximately 10 – 15 minutes, the bridge tenders have a lot of downtime. When not pushing levers or logging the openings, they occupy their time working on laptops, reading, playing guitar, or simply contemplating. “It’s a thinking job,” Mike says, who, with four years on the job, has observed and contemplated many of the ins and outs of the bridge operations. It takes 12 seconds for the traffic gates to come down, Mike has counted, and when there are four bars visible on the Ferry Street Bridge pier, the Mary Colman oyster boat can pass under the bridge without it opening.

For Anthony, the currents are the most captivating observation. “If you’ve never experienced the power of the river, walk across one of the bridges at the tide change,” says Anthony. “Sometimes you can actually hear the current from up here inside the house.” For the bridge tenders, keeping a keen ear and eye on the currents and other environmental factors, such as snow, ice and wind come with the territory. They adjust the swing bridge openings based on the water velocity and during heavy snowfalls won’t open the bridge due to the excess weight.

At every opening, regardless of the weather, the tenders must stay alert. We listen while the bridge opens for certain noises that might indicate a problem, explains Bob. “Each of the bridges has its idiosyncrasies,” he adds.

Bob’s been working the bridges for eight years now and, while he admits he grows accustomed to the views, he still harbors a great appreciation for his office. “It’s a nice situation to work in, to be by the water.”

Photos by Ian Christmann